Earlier this week, I returned from a long weekend in Story, Wyoming, where I attended the Doomer Optimist Campout at the Wagon Box Inn. For those unfamiliar, Doomer Optimism events—organized by Ashley and Patrick Fitzgerald—bring together people concerned about societal collapse, ecological degradation, or the fragility of modern systems, but who are also committed to constructive, grounded action and building local resilience.

These events are truly fascinating. They draw an unusually diverse crowd: Traditional Latin Mass Catholics and Eastern Orthodox converts, Mormons and agnostics. You meet people living off the land with minimal technology alongside others developing new tools in urban coworking spaces and investing in AI startups. As Leighton Woodhouse has observed, these events create a genuinely convivial space for dialogue and disagreement.

Grant and I attended a similar gathering last year in Margaretville, New York. (You can read Grant’s account of that event here.) In fact, the Savage Collective is now working with Ashley to host an event in Ligonier, Pennsylvania, this coming November. I strongly encourage you to attend. These events have been life-changing for me.

I wanted to share a brief reflection on the weekend.

One theme that stood out was the wide range of perspectives on AI. On one side was Paul Kingsnorth—perhaps the most prominent anti-Machine writer on Substack—who regularly attends these gatherings. To call him a tech skeptic is an understatement. Kingsnorth sees the internet as a portal through which ancient demonic forces are being ushered into the world. Read his short story The Baselisk to get a flavor of this.

On the other end of the spectrum were John Stokes and Julie Fredrickson, who worked to demystify AI, arguing that it is essentially just a tool—and not even a very smart one. There was no “sky is falling” with either one.

Stokes, trained as a theologian, began his talk by recounting how early Christians adopted the codex—essentially the book form we know today—over scrolls. The codex was more portable and practical, and its adoption played a key role in the rapid spread of Christianity.

He went on to argue that AI is similar: not intelligent in itself, but rather a multiplier of whatever it is trained to do. Just as we moved from text-based to graphical user interfaces, AI represents the next leap in how we interact with digital systems. And like other past technologies, people are quick to project consciousness or agency onto it. But underneath the breathless hype, there’s nothing magical going on.

Stokes emphasized that once you understand what’s happening under the hood, the mystique of AI vanishes. It becomes a process you can learn, manipulate, and harness for useful ends.

This conversation reminded me of arguments brought to light by John F. Kasson in Civilizing the Machine: Technology and Republican Values in America, 1776–1900. Stokes and Fredrickson’s views echoed early reactions to the first machines.

Kasson points out that early American machines were often built with ornate finishes—polished wood, decorative trim, or gleaming metal casings. The goal was to conceal the machinery’s inner workings from the average user, dazzling them with aesthetics and keeping the actual function out of sight. Kasson writes, “As engineering grew more intricate and machines adopted casings and housings that masked their working parts, it became difficult for all but the most knowledgeable observers to judge their performance readily.”

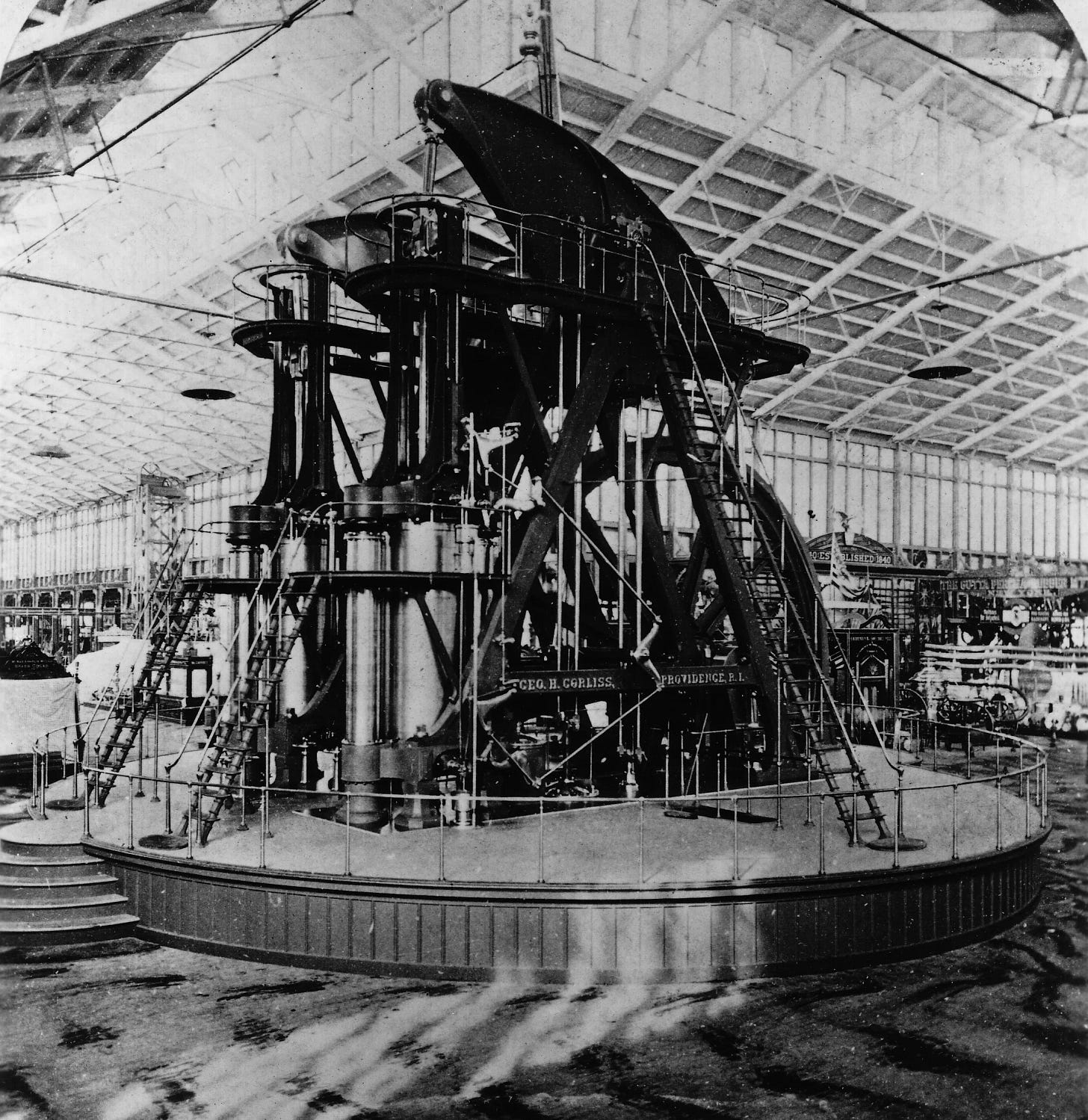

One striking example was the Corliss steam engine, showcased at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. Standing 39 feet tall and weighing 680 tons, the engine powered the entire exhibition. Fairgoers were awestruck:

Nineteenth-century engineering critics protested that the Corliss engine represented no important technical innovations and even suggested that with a few improvements its power and efficiency might be vastly increased. But fairgoers did not approach the engine as an immaculate work of engineering, to be judged by its efficiency alone. Rather, in a way characteristic of popular reactions to powerful machinery in the nineteenth century, their descriptions frequently became incipient narratives in which, like some mythological creature, the Corliss engine was endowed with life and all its movements construed as gestures. The machine emerged as a kind of fabulous automation—part animal, part machine, part god. In the melodrama which various visitors projected, the engine played the part of a legendary giant, whose stupendous brute force, they congratulated and titillated themselves, was harnessed and controlled by man.

Sound familiar? I can’t help but feel we’re in a similar moment with AI—a tool whose inner workings are hidden from most users. While there's no actual magic or consciousness in a large language model, the public response is often one of awe, and even reverence.

As many of you know, I’ve spent my life around old cars. I’ve handled the hidden components—piston rings, torque bolts, snap rings—that hold them together. To someone who understands how a 350ci small block engine works, there’s nothing mysterious about it.

And yet, there’s something nearly liturgical about the process. The repair manuals read like sacred texts. When you fire up a muscle car, hear the throaty exhaust, and slam the accelerator to get sideways on an empty road, “hallelujah” feels like the right word.

But most people don’t rebuild engines. They just drive to work. They don’t check valve lash or adjust timing—they leave the inner workings to the experts. And that’s what concerns me about the narrative that AI is “just a tool.”

In theory, yes. But in practice, AI’s workings are closed off to most people. Its usefulness requires a level of technical fluency that’s out of reach for the average user. Who has the time to learn all that?

I’m sympathetic to efforts to demystify AI, and even relieved by them. But on a practical level, I can’t shake the sense that this technology represents another widening gap between the programmer and the programmed. And I worry that, collectively, our response will be an even louder “hallelujah”—not to something we understand, but to something we don’t, and which increasingly appears to us as a god.

My personal crusade in this matter: stop calling it AI and start calling them LLMs or image generators or whatever. Get rid of the sci-fi terms and we’ll cut through the sci-fi mythos.

Thank you for the article. The key is that we humans can turn anything into a god, especially dazzling technologies with their aura of (cultivated) mystique. So I'm all for desacralising technology. However, humans are notoriously in deep need to believe in some 'god', to believe in something greater than themselves. And having desacralised Nature, Mother Earth, technology conveniently fills the gap; AI being the latest 'face' of the techno-god. And yes, in its time steam-engines played that role. And D.H Lawrence and others had a few things to say about that.