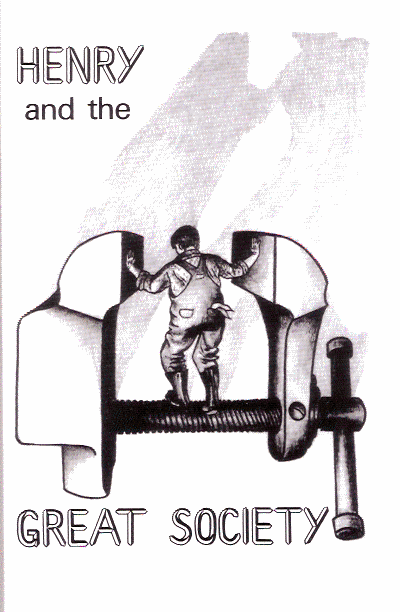

Machine Capture in Three Acts

Lessons from Henry and the Great Society

A minor goal of the Savage collective is to make one of our favorite books, Henry and the Great Society, a cult classic. We stumbled on this book quite by accident. During his childhood, Brandon’s family would take minivacations to Amish country in Eastern Ohio. On one of those lazy shopping days, he perused a small used book sale at a homestead farm. He purchased the book on a whim and remembers reading it as young teen. Even at that time, he sensed the significance of the book but lacked the context to fully appreciate it. Recently, he picked the book back up. Reading it again, he realized how much it aligns with Savage Collective’s goals. He began to wonder how much his subconscious had been impacted by that book all those years ago.

In our opening essay, we quoted from David Foster Wallace’s 2005 commencement address at Kenyon College. This address is legendary in our circles, so expect to see it again. Wallace starts the address with a joke:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”

To Wallace, this joke tells a deep truth that “the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about.” The Machine most insidious effect is that we are all born into it but often cannot see it for what it is. One might ask “What the hell is the Machine?”

Henry and the Great Society is intended to help you wake up and see the Machine. Written by HL Roush in the late 1960s and published by a small press (Pathway Publishers) in Indiana, the book remains in print to this day. Very little is known about HL Roush. A basic internet search reveals almost nothing about him.

Henry and the Great Society is a novella (115 pages) best understood as an extended parable. There is no literary nuance with Henry and the Great Society but has a clear lesson for the reader. Many might find the heavy-handed narrative too obvious. But Roush is trying to jolt you awake. Flannery O’Connor wrote “When you can assume that your audience holds the same beliefs you do, you can relax and use more normal means of talking to it; when you have to assume that it does not, then you have to make your vision apparent by shock -- to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures.” This is Roush’s approach to writing.

Henry Jenkins is a small hold farmer somewhere in the Midwest, likely Indiana. He lives with his wife Esther and their sons, Brent and Jeff, on a farm passed down through his family for generations. At the outset of the story, Henry’s life is quite contained. The family toils together to maintain a subsistence existence, the farm providing their needed food and resources. They sell a small amount of excess produce at the local market to purchase some extra luxuries. The farm is simple, lacking electricity and indoor plumbing. Their lives are filled with hard work but also marked with friendships and associations with their neighbors through church and the local farming community. Evenings are spent singing and telling stories around kerosene lamps. The Jenkins family would fit well in Wendell Berry’s Port William membership.

Rousch’s parable shows how the Machine (to Roush “The Great Society”) slowly but surely captures the Jenkins family over the course of several years. To understand this novella, you must first recognize that, for Roush, the Machine represents an orientation of the heart. He grounds his own understanding of the Machine in Christianity, identifying greed as the central vice underlying all crises within the Machine age. He draws extensively from the book of 1 Timothy:

Of course, there is great gain in godliness combined with contentment; for we brought nothing into the world, so that we can take nothing out of it; but if we have food and clothing, we will be content with these. But those who want to be rich fall into temptation and are trapped by many senseless and harmful desires that plunge people into ruin and destruction. For the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil, and in their eagerness to be rich some have wandered away from the faith and pierced themselves with many pains.

In fact, the entire final third of the book is dedicated to a theological interpretation of the Machine. Those without Christian commitments might find these sections tiresome, but Roush considers them essential for understanding the Machine’s deeper workings. Paul Kingsnorth, a contemporary prophet of the Machine, makes a similar argument by asserting that want (akin to greed) is the fuel of the Machine. He describes his own realization of this truth in his essay “Want is the Acid”:

There it was, all of a sudden, right in my face. Eating. Drinking. Buying colourful things. Boats, vans, bikes, beer, steak, new clothes, second hand clothes, burgers, chocolate bars, old castles, stately homes, cappuccinos, pirate adventure parks, golf courses, spas, tea rooms, pubs. Food, drink, fun, entertainment, games, probably some sex somewhere in the mix. All of it came together suddenly into a kind of package of sensory overload and I saw that this was what we were, what we had become without really thinking or planning it. Stimulating the senses, then reacting to the stimulus: this was what our society was all about. Feeding the pleasure centres, spending and spending to keep it all coming at us.

In a previous essay, we also described the Machine as an orientation of the heart toward the destruction of all obstacles and the elimination of all suffering. All of these articulations speak to shared metaphysical underpinnings of a Machine culture focused on luxury, control, comfort, etc.

With that substructure in place, the story of Jenkins’ capture by the Machine unfolds in three acts.

Act 1: From Wants to Needs

The process of Henry’s capture starts as the Machine helps him discover new wants that he never really knew existed. Throughout the novella, Henry and his family are told repeatedly by friends, neighbors, government agents, and business representatives that they deserve the “good things in life,” which are the products, devices, and services that were newly developed and widely disseminated during the post-War economic boom. Of course, the key weapon of the Machine is to make sure that one these devices simultaneously and conveniently acts as an advertisement machine. In Henry’s case, the introduction of the television was the accelerant that quickened the process of want-generation.

One of the most important technologies that the Jenkins adopted was electrification at the farm. The family had spent many happy years without electricity, working based on the sun and spending evenings huddled around their kerosene lamps. For so long, Henry and his family never knew that they even wanted electricity. But within 15 pages, the electricity became a deep a need.

Throughout the story, in response to Henry’s fears, Esther Jenkins is constantly saying that they should not be scared to get these “good things” in life because “There is nothing to fear in progress. It can only change those who want to be changed.” As the parable shows, this is folly. The things we use change us dramatically. Often, we are so focused on what technology can do, we forget that, as subjects, the technology is doing something to us. Electrification is a great example. After electrification, Henry slowly added more and more tasks and more and more wants that only could be achieved by more and more electrification. Soon, his life was so dependent on the electricity that now he “needed” it. His life was now shaped around electrification. The family was inevitably changed whether they wanted to be or not. That is the biggest accomplishment of the Machine turning their self-created wants into our needs.

Act 2: From Production to Consumption

With the accumulation of new wants morphing into new needs, the Jenkins family experienced an important transformation. They went from a family within a household marked by production to one marked by consumption. This is a very important and nefarious transformation. The Jenkins were once a family that produced their own food, repaired their own equipment, built their own home, and provided their own energy. As their wants and needs became greater and more complex, they were purchasing and accumulating more goods that required energy inputs derived away from the home and were too complex and sophisticated to be produced or repaired within the home. Therefore, the epicenter of production and agency moves away from the Jenkins to a complex constellation of corporations and government agencies located in far-off places. Brandon gets at this important point of the outsourcing of repair in his most recent essay. This is an exceptionally important turn. Once the household is primarily seen as a place of consumption rather than production, the nature of the household changes dramatically. The Machine can now make its final move of accumulation.

Act 3: Accumulation

Once the household is primarily seen as one of consumption, the money, time, and capacities of the household are oriented toward increasing consumption. The Machine can now more easily accumulate into itself. The Machine begins to accumulate wealth. Very quickly Henry realizes that these new needs must be paid for, and their costs slowly outstripped his income. This is especially true in the Jenkins home where there was little “income” as the production of their home is largely for internal use. To accommodate these increasing wants, Henry was required to build up debt. At first, the amounts could be easily financed with monthly payments. But, as the wants expanded, the debts began reproducing like rabbits. Ultimately Henry is forced to mortgage his farm to pay off the consumer debt. Now Henry’s one source of productive wealth is no longer his. It has been accumulated into the Machine and used to finance a bank for the purposes of men in glass and steel towers.

Second, The Machine begins to accumulate Henry’s time. Much of Henry’s time is now spent fixing his new devices and talking with bankers. Henry spends very little of his time actually mowing his fields and tending to his flocks. Fortunately, now with the electrification of the farm, he can work in the evenings. To catch up with the work that he put off during the day, he does his barn work in the evening under the glow of the bulb. His wife, Esther, begins to find “worthwhile” activities in the evenings while Henry is working in the barn. They no longer really need Esther anyway because she can serve the family TV dinners from the deep freeze. Accumulation of time into the Machine is a distinctive mark of modernity. Hartmut Rosa refers to this idea as “social acceleration.” With the growing magnitude and complexity of our various “needs,” we experience a speed-up in the number of tasks we must perform. Those devices and procesesses meant to give us more time have actually taken it away. Remember, email was originally developed as a time-saving tool.

Third, the Machine begins to accumulate Henry’s capacities. Henry has always been a very capable man. He fixed his implements and executed the needed repairs on his farm. However, as he aquires more and increasingly intricate devices, he is less capable of fixing them. He has to call a 1-800 number to ask them to send an expert technician to fix his stuff. Again, Brandon talks about this at length in his recent essay “The True Cost of Outsourcing Repair.” Likewise, because he is working in the evenings in the barn and TV is constantly blaring, he no longer plays music or tells stories to his kids. This once capable man is incapable of doing anything anymore. His capacities have been accumulated into the Machine. Finally, to secure “the good things in life” within his dwindling time, he is forced to take a job at a factory. His job now consists of repeatedly drilling a single hole into a slab of plastic. This man who was once capable of running a farm, fixing things, and building his own barn, whose life was categorized by limits yet somehow more agency, is now relegated to drilling holes.

Slaves to the Machine

Where does this leave Henry? He now has deep set of needs that he never had before, fully dictated by the desires of the Machine. These things that he has collected require him to transfer his wealth to banks, give away his time, and surrender his human capacities.

During a particularly grueling day at the drill press, Henry takes a break, lays down on the factory floor, and has an epiphany:

He could hear the continual hum of the plant, and it suddenly reminded him of the hum of the house. And how he had discovered that night that he was a slave to an inhuman machine that would destroy him eventually. Now the hum of the plant confirmed what he already knew and would not admit: He was hopelessly trapped.

The whole novella ends tragically. Ultimately, Henry dies in a car accident on the way home from the factory. Rousch leaves open the question of whether Henry took his own life. But Roush is clear on one point, at the end, Henry was as a slave to the Machine master.

Wow, cross-pollination of this with another post today:

https://naomiwolf.substack.com/p/brian-reisinger-land-rich-cash-poor

I hadn't known about the novella on Henry, many thanks for it.

Ugh. The good kind of uncomfortable. What to do when you realize you are already inside the Machine? I have a quote on my wall by DFW that says "whatever you get paid attention for is never what you think is most important about yourself". I wonder how many of us it would take to live what we think is most important before the Machine tries to shut us down. That might be fun...