On not being a cubicle monkey

Meaningful work in an age of bullshit jobs

One of our goals at the Savage Collective is to provide a context for new writers to develop their trade. Today’s post is written by a new contributor named Anthony Scholle. Anthony is a senior philosophy student at the University of Pittsburgh and a working automotive mechanic. He is also doing something that won’t compute. He and his new bride will be welcoming their first child months after he graduates from college. Anthony wrote this piece as part of an independent study here at the University. We’re grateful for his contribution.

Grant teaches a freshman seminar course that serves as a sort of “introduction to college.” It offers him a lot of latitude to explore various topics. Recently, he asked his students to define “work.” Many described it as something they are “forced” to do, something that will be “boring,” a “requirement,” and primarily a way to earn the money needed to live the rest of their lives.

I’m an auto mechanic, but I am also a college student. I’ve noticed a similar perspective among my peers, both in person and online. The idea that work is inherently unpleasant and something to endure is increasingly common.

These anecdotal observations align with evidence from the recent book Generations by Jean Twenge, a psychologist and an expert on the impact of technology on generational differences. Twenge argues that Gen Z has “a work ethic problem,” viewing work as less central to their identity and life. Subsequently, they are less willing than previous generations to work hard. Many are highly skeptical that they will find work satisfying. Twenge summarized these findings in a recent Substack post.

In the wake of COVID, many in Gen Z posted on social media that they were practicing "quiet quitting.” They would go to work because they needed the money, but they wouldn’t actually be doing the work. Many older generations bemoan this apparent lack of work ethic. But I think Gen Z is actually on to something. Trends like quiet quitting are revelatory. Realizing that they could remain employed while not doing their jobs, Gen Z confirmed their suspicions that they had been swindled into doing pointless work.

The conclusion many draw is that work itself is pointless. But I would argue otherwise: work is not pointless. Pointless jobs are what we hate, not work itself. What’s the difference? Simply put, we’ve conflated the concepts of work and jobs, and this confusion has unfortunate consequences.

What then is work? In its most basic sense, we do work when we apply our unique human capacities—often in combination with technology—to transform the raw materials of the world into something that benefits ourselves and our fellow man. Good work is inherently oriented toward human flourishing. You can read more about how we define human flourishing here but in short human flourishing is a good life well-lived. Flourishing is the internal good that defines work, giving it its very nature and being. In this sense work is unavoidable insofar as we are meant to have agency in the world and to love our neighbors. We cannot even conceive a world where this kind of work is not done.

Work, then, is the primary means by which we love our neighbors. Good work is necessarily an expression of love toward the world. To love another person is to will his good. To will another person's good is not only to want it for them, or to hope they get it, but to act and to do real work in the world that moves him toward that good. We will the good of other people, of our communities, and the world at large through our uniquely human God-given capacities.

At the same time, properly oriented work fosters the flourishing of the worker. Good work makes us more authentically human by developing human capacities and achieving the natural goods of the human person. Ideally, good work helps us to grow in virtue; in physical, mental, moral, and spiritual excellence. If we reject work as such, we reject one of the primary ways that we love our neighbors, grow in excellence, and achieve the basic goods of human flourishing.

I am an automotive mechanic. So, in the way we usually speak, I am not "at work" as I write this piece. I am not getting paid for it and no one hired me to do it. On the other hand, tomorrow I'll wake up early and head into the shop, I'll “go to work,” but that’s not all the work that I will do during the day. I won't get paid to make my wife dinner, or to help my brother install a new toilet. These things—whether writing, cooking, or plumbing—are clearly still work, still labor. But I do not do these things for a wage. I do them because I love those people that my work benefits. Herein is the difference between work and a job. Jobs are the portion of work that we are paid for. When I get up tomorrow morning and put on my uniform, I will be engaging in my job which is only a small part of my total work. But it is by no means all the work that I do.

It’s helpful to consider the etymology of the word job. One of the earliest recorded uses of the word refers to “the amount a horse and cart can carry at one time.” Over time, job came to mean a discrete amount of work. This usage echoes the Mid-Renaissance phrase “a job of work.” In fact, this language fits the trades so well because our work is inherently tangible and finite. After driving the last screw, tightening the final bolt, or nailing the last shingle, the job is complete.

Now, a “job” is the work we are paid for. Industrialization and commodification have conflated jobs with work, making the only true work the work for which we get paid.

So, if we are thinking about good jobs, we certainly need to consider financial and other remuneration. Sure, good jobs, at a minimum, should provide a living wage. Ideally, they enable a single income to support a family without incurring excessive debt or fostering excessive luxury. Such jobs should offer good benefits, opportunities for advancement, and enough stability to allow for some leisure.

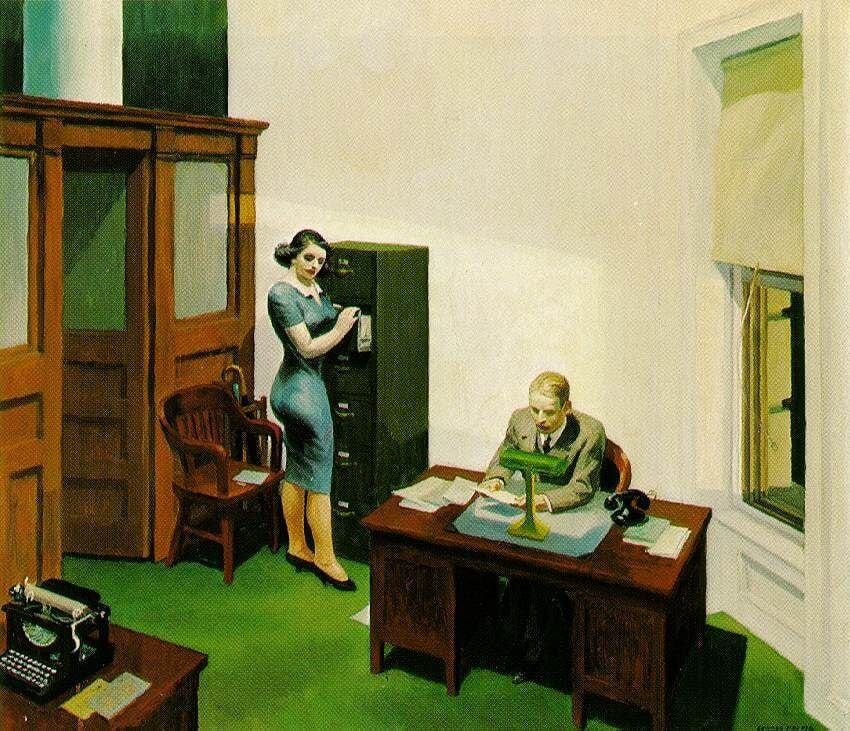

But, when Gen Z talks about hating their jobs. I don’t think it has much to do with these remunerative aspects of work though I am sure many of us want better pay and benefits. I think the critique exists at a much deeper and fundamental level. Namely, we sense that these jobs do not have the characteristics of good work. This is especially true for the sort of cubicle monkey “information economy” jobs that many of my university colleagues will eventually hold.

Why is this? First, many contemporary jobs lack a tangible connection to human flourishing. David Graeber, in his essay and later book called “Bullshit Jobs”, argues that the industrial revolution’s efficiency gains should have drastically reduced work hours. Instead, consumer culture escalated the need for income, fueling the creation of what he called "bullshit jobs"—roles invented not to fulfill true human needs but to sustain Machine capitalism.

He wrote:

But rather than allowing a massive reduction of working hours to free the world's population to pursue their own projects, pleasures, visions, and ideas, we have seen the ballooning of not even so much of the ‘service’ sector as of the administrative sector, up to and including the creation of whole new industries like financial services or telemarketing, or the unprecedented expansion of sectors like corporate law, academic and health administration, human resources, and public relations. And these numbers do not even reflect on all those people whose job is to provide administrative, technical, or security support for these industries, or for that matter the whole host of ancillary industries (dog-washers, all-night pizza delivery) that only exist because everyone else is spending so much of their time working in all the other ones. These are what I propose to call ‘bullshit jobs’.

I think Gen Z gets this even if we can’t articulate it.

Even jobs that seemingly contribute to human flourishing are increasingly disconnected from their tangible outcomes due to automation, digitization, and extreme specialization. Rarely do we see how our work contributes to actual human good. For instance, a commercial baker might never touch dough but instead presses buttons on a bread-making machine, losing connection to the craft itself. The baker, then, ceases to be a baker and becomes a machine operator. Now he does not need to develop the skill of breadmaking, but of efficient button-pushing. A person who flips a switch on a machine is much more likely to be treated as a part of that machine, as an object of work, as opposed to a person whose input, skills, knowledge and creativity are integral to the creation of some good.

Such modern jobs can strip workers of their agency and skills. Beyond automation, bureaucratic systems and surveillance often constrain workers, making their roles even more impersonal and frustrating. Brandon’s recent article Nonsense Fatigue sheds light on this problem, illustrating how corporate systems layer jobs with excessive rules, surveillance, and inefficiencies. These structural issues make bad jobs nearly unbearable, robbing workers of the opportunity to develop and exercise their capacities in meaningful ways.

Finally, modern jobs capture increasing amounts of our time and concern. Technologies like email, once celebrated as labor-saving, now consume hours, following workers home and into personal time. Flexible work arrangements, instead of creating “family-shaped jobs,” have resulted in “job-shaped families.” Likewise, service jobs make emotional connection—the worker’s ability to project warmth, empathy, or love—a product. At a recent doctors appointment in a large hospital, I saw a computer sleep screen graphic explaining to employees how to make eye contact and greet people in the hallways. This phenomenon, sometimes referred to as the “managed heart,” is deeply taxing and contributes to high rates of burnout. It’s increasingly difficult to simply leave work at work.

Gen Z seems to recognize that modern jobs have enormous potential to suck our energy. Why dedicate a life to something that fails to contribute meaningfully to the world and one’s personal growth and requires constant attention and care?

Such critique, however, should not lead us to denigrate work itself. To do this would be to disregard our ability to actualize love and goodness in the real world. But it should lead us to push for better jobs. Jobs, like all other work, should be done out of love to actualize some real good in the world. Pointless jobs make that impossible.

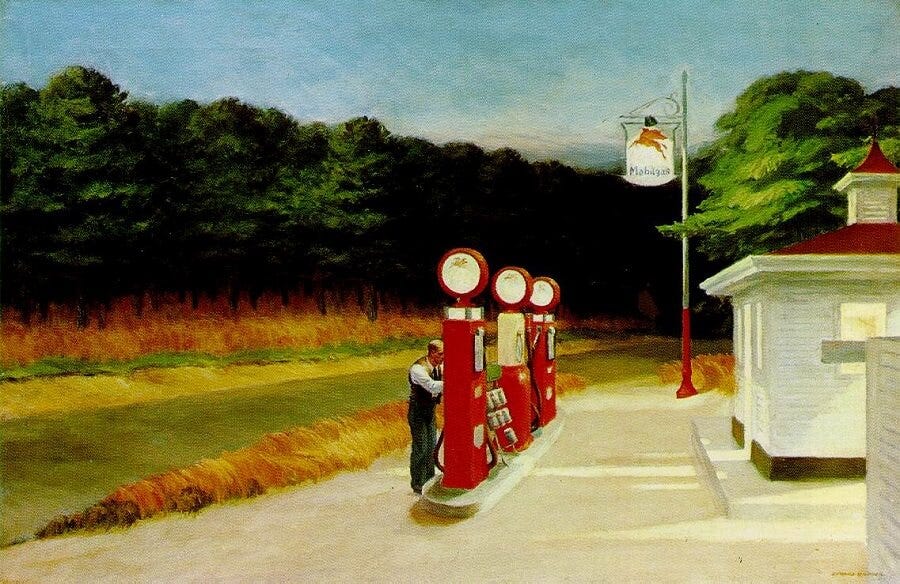

I feel extremely lucky. I think that I have largely found my way out of the monotony of pointless work. My experience both as a mechanic and college student have shown me that there is hope in the trades. Even as technology creeps towards taking our skills, the trades contribute to human flourishing in a way that pointless jobs cannot. When we build and fix things that we can lay our hands on, when we can walk away at the end of the day and say “I did that,” when we use our creative human capacities to solve real problems for real people, we bring the aspects of good work into our jobs. These jobs can be rays of hope in a world so discontented with the effects of their jobs. For this, I am grateful.

There is much talk today about the end of work. Derek Thompson of The Atlantic has written frequently about the post-work future. He is not quite right. What he is speaking of is a post-job future. And in some ways, it is probably for the better to get rid of all the pointless, life-sucking jobs we hate but perform to keep the Machine humming. But work will remain central to human flourishing and to our integration as embodied souls, as whole persons, oriented toward the Good. Jobs may fade, but there will always be work as we act to love our neighbors.

Great work.

I think a lot of this problem comes down to a loss of locality in work. It’s easy for a baker who sees his neighbors coming in to get their bread for the day to recognize how his work is meaningful. It’s a lot harder for an insurance agent to see that sort of meaning when the people they do help are so disconnected from them. (And, of course, plenty has been said about the good and bad of insurance over the past week)

I imagine being a mechanic is one of the better professions to keep that sense of locality—you’re probably still working with people you know from communities you’re part of.

I greatly, greatly enjoyed this essay. I've just finished reading Matt Crawford's Shop Class as Soul Craft, and this did a great job of applying the same ideas to what journalism's cubicle monkeys call "timely issues." My next essay may well be a response. I endured a year in a state university admin job and was shocked at how low the bar was set. I had to invent tasks to do, which included teaching myself basic web design so I could update the department's ag econ blog from looking ca. 2001. It wasn't so I could get a raise (the state system ensured raises were infrequent and minimal). It was boredom.