In 1892, the chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company, Henry Clay Frick, decided to cut the wages of the workers in Pittsburgh mills. This led to the Battle of Homestead, wherein Pinkertons hired by Carnegie fought with striking workers who were trying to defend their jobs and provide for their families. At least 16 people died.

The following year, Antonín Dvořák’s 9th symphony, “From the New World,” was performed for the first time at Carnegie Hall in New York City. Dvořák wrote the symphony while he was director of the National Conservatory, an institution funded by a number of wealthy philanthropists, including Andrew Carnegie. This past weekend, I ran into

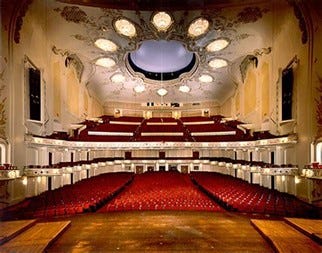

at a performance of Dvořák’s “New World” by the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra at Heinz Hall in the aptly named "Cultural District" of Pittsburgh.We realized that it is both of our favorite symphonies. If you don’t know it, stop reading now, go listen to it, and come back. It is a pure masterpiece, from the soft violin and flutes, just barely playing at certain points, to the most gradual and magnificent crescendo in all of music in the fourth movement. While you might expect an effete professor like Grant to appreciate the symphony more than an auto mechanic, each of us appreciate it a great deal.

Authors at the Savage Collective have been writing about the importance of bottom-up culture creation as a form of anti-Machine resistance. In a recent guest post, our friend Patrick Koroly wrote about the grassroots cultural creation within the pages of the The Mill Hunk Herald, which featured essays, stories, and poems written by steelworkers. He identified the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra as a form of elite top-down boardroom cultural management. I thought Patrick’s point was not only insightful but poignant. I agree that bottom-up cultural creation is necessary to resist the Machine and its ways. Attending the symphony definitely didn’t feel like resistance.

But I do love the symphony. In a comment on Patrick’s essay, I wrote, “The ballet isn’t as real as sitting around with your neighbors and singing ‘Johnny Leave Her’ until bedtime.” I think this is true, but I have to admit that the boardroom has helped create some beautiful things in our city. It isn’t really economically feasible for symphonies to be written without the support of wealthy patrons. And “though a grassroots symphony or opera might be possible, it’s clear that it’s incredibly difficult and verging on impossible.”

During the PSO’s performance, the conductor told us that he had met Antonín Dvořák’s great-great-granddaughter and asked her to record a video to show at this performance. In it, she told the story of her grandfather coming to America. Apparently, he did not want to; he preferred to stay in the Czech countryside and write his music. But “the money was good,” so his wife secretly sent off the signed contract, forcing him to go to New York. Without his wife, without the apparently generous contract, without Carnegie’s support of the National Conservatory, without his namesake theater, without the destruction of the Pittsburgh steel industry and the “cultural rebrand” that Patrick outlined so well, without all of this Machine support, I would have been deprived of one of the best musical performances I have ever seen.

This seems to highlight the fact that history fertilizes the present with nutrients necessary for both the seeds of destruction and for the new way forward; for the wheat and the chaff. In his book Hope Without Optimism, Terry Eagleton states that we need to understand “how damagingly the past is interwoven with the present, but also how it can furnish us with precious resources for a more promising age to come.” He is speaking mostly to the blind optimism of those who see nothing but good in Machine “progress.” He argues that Machine optimists simply “(trust) that one aspect of human nature—our ability to come up with smart new ideas—will outweigh our predilection for cruelty, self-interest, exploitation, and the like.” Namely, those who believe the Machine will inevitably bring forth a promising future must contend with the fact that the gains that we have enjoyed in sectors such as healthcare and infrastructure necessarily destroyed other conditions essential for human flourishing. We cannot innovate our way out of human realities. As my father often likes to remind me: there are no technical solutions to moral problems.

Sometimes, we anti-Machine writers fall prey to the opposite predilection—that we are unable to see what we’ve gained from the Machine. Instead, we need to face the fact that the dehumanizing aspects of the Machine are historically entwined with the good that it has brought us.

At the Savage Collective, we are trying hard not to be nostalgists. We realize that the “good old days” and their systems were full of people just as broken as we are today. Instead of dwelling on the past, though, we take the world as it is and try to find within the Machine the very resources that we need to get outside of it. The Machine is what we live in. It is pervasive and largely inescapable. Our mission is to resist the dehumanizing aspects, but that means being thoughtful and crafty about how we do it. We do not need to die on every ant hill. When the Machine gives us something true, good, or beautiful, we need not cast it out. We can appropriate it for Machine resistance. We use the Machine against the Machine. We can be creative about how we use the infrastructure created by the Machine to build some sort of bottom-up cultural revitalization. Because Carnegie didn’t write the symphony—he just paid the man who did.

Not sure I entirely agree.

We're riding a comfortable (for most readers) fast train headed toward a terrible cliff. The fact that the piped in music is good doesn't change that, so I don't know that I can comfortably accept the statement that the Machine does also facilitate "good"...I understand the larger point, though, that sorrow and joy are mixed everywhere, and we can't refuse to see or hear something or appreciate it, if its genesis is not spotlessly pure.

Plus, I think , good as the New World is, if you know the mechanism of its production, you can also hear in it the despairing cries of starving steelworkers and their families. I'm not saying its only the New World is like that: the mechanism of most official culture ensures that many things are so

Wow, I'm getting responses. How about that?

I suppose I do have one question: What "ant hills" should we die on? We can acknowledge that things like great films, the symphony, museums, sports leagues, or whatever are all good things but also almost unthinkable without the bureaucratic dominance of the Machine. There's merit to all of them, things to be appreciated to all of them, but if they're good things that are inextricably tied to the Machine...do we have to give them up?

Of course, most of them are not actually inextricable--you can have a sports league without having a massive industrial-bureaucratic apparatus--but it's hard to resist the Machine while just accepting all the things that it offers.

I do have hope that most of these things can become a form of creative resistance, but I think that has to start with creating new centers of cultural power--ones that exist outside the logic of bureaucracy and dehumanization. But I'm still not sure we can properly call it "resistance" to just enjoy how good the symphony can be.