Culture making as resistance

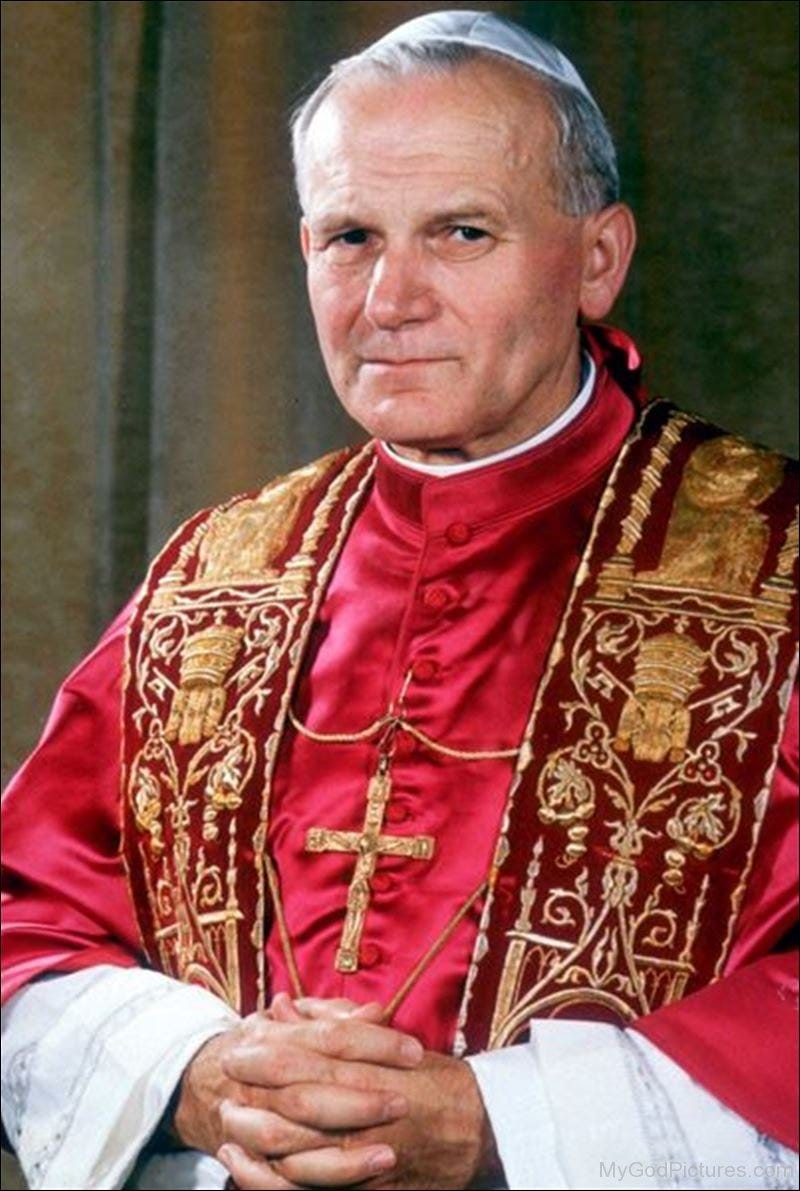

Wojtyla and the Rhapsodic Theater

The Savage Collective participates in broader “anti-Machine” discourse that includes many familiar Substack authors. Although not a rule, the anti-Machine discourse tends to take on a negative posture calling attention the dehumanizing nature of the Machine—how the gears grind up both people and culture.

In this way, much of the discourse is prophetic and revelatory, which is crucial. The Machine thrives on our tacit participation and acceptance. Most people remain oblivious to its presence and workings. However, such a posture creates a tendency within the anti-Machine project to focus solely on what we hate, spending much less time on what we love, what is worth preserving and creating.

Once our eyes are opened to the dehumanizing nature of the Machine, we need a way forward. We must ask: How do we act in response to the Machine? This question occupies me deeply. At a recent anti-Machine conference in Margaretville, NY, my talk focused on my own response as someone embedded in the Machine—namely, higher education. Should I get out? Sabotage it covertly? Quietly quit? My talk raised many questions but offered few answers.

As I wrestled with this, I revisited George Weigel’s biography of St. John Paul II (JP2). My wife and I, relatively recent Catholic converts, have found inspiration in JP2’s life. I took him as my confirmation saint, and this book played a significant role in my conversion. If the Church could produce someone like JP2, perhaps it could help me become more humble, patient, and courageous.

JP2’s public ministry was shaped by his early experiences in Nazi-occupied Poland. When the Nazi War Machine rolled into Kraków in 1939, Karol Wojtyla (JP2’s name before becoming Pope), then a student at Jagiellonian University, was forced into manual labor at a limestone quarry. I suspect this experience shaped his lifelong concern for workers. But, as they labored, Wojtyla and his friends faced the same question we ask today: How do we act in response to this Machine?

Together, they joined UNIA, a clandestine resistance group. UNIA unified various Catholic youth organizations and acted against the Nazi Machine on multiple fronts. Like today’s anti-Machine writers, it played a prophetic and revelatory role, producing pamphlets and editorials to awaken the conscience of the Polish people to the horrors of the Nazi Machine.

But UNIA didn’t stop there; it also embraced active resistance. Part of that active resistance was militant. Its militant branch contributed nearly 20,000 young Poles to the Polish Home Army, the primary militia resisting Nazi occupation. They sabotaged transport lines, assassinated collaborators, and targeted Gestapo officials.

Militant resistance can be appealing. There’s something in me that bends toward militancy. Several years ago, Brandon gave me a document he thought I’d appreciate: Industrial Society and Its Future. I found its critique of industrial capitalism compelling—until Brandon gleefully informed me, I had just praised the work of Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber.

Similarly, many of us chuckled nervously when the intellectual interests of Luigi Mangioni’s, alleged killer of UnitedHealthcare’s CEO Brian Thompson, began to emerge. He echoed concerns about technology shared by figures like Jonathan Haidt. He was concerned about fertility rates. I share some of Luigi’s critiques of the American healthcare system—its greed and transhumanist theology make it quintessentially Machine. In fact, my father called me and asked, tongue in cheek, if I knew Luigi. “He went to Penn (my alma mater), and he sounds just like you!”

Even less violent forms of resistance, like eco-activists defacing art or “quiet quitting,” reflect this tendency toward militant action. There’s something to admire in their defiance, but many of these responses ultimately feel destructive, even sinful.

I’ve become convinced that militant resistance is not the way forward. Many such actions are morally indefensible, involving violence, deceit, or the destruction of beauty. I am not necessarily against assassinations and destructive resistance in principle. I could easily be convinced that the UNIA approach was justified. However, the actions of Uncle Teddy and Luigi were simply murder.

But, my biggest concern is that even when justified—such as UNIA’s actions against clear evil—militant resistance to the Machine seems futile today. The Machine is insidious precisely because it is pervasive and invisible. Unlike the Luddites, who could smash physical looms and confront specific owners, we face an abstraction. Killing a CEO or smashing servers achieves little when the system quickly adapts. The Machine transcends any individual person or structure. You can’t kill an algorithm.

I was reminded of this recently as I was reading the Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck.1 In a particularly poignant section, several tenant farmers are being evicted from farms by the landowners to be replaced by tractors and large-scale production. Their conversation with the landowners reveals the abstract nature of the Machine which Steinbeck calls “the Monster.”

And now the squatting men stood up angrily.

Grampa took up the land, and he had to kill the Indians and drive them away. And Pa was born here, and he killed weeds and snakes. Then a bad year came and he had to borrow a little money. An’ we was born here. There in the door our children born here. And Pa had to borrow money. The bank owned the land then, but we stayed and we got a little bit of what we raised.

We know that—all that. It’s not us, it’s the bank. A bank isn’t like a man. Or an owner with fifty thousand acres, he isn’t like a man either. That’s the monster.

Sure, cried the tenant men, but it’s our land. We measured it and broke it up. We were born on it, and we got killed on it, died on it. Even if it’s no good, it’s still ours. That’s what makes it ours—being born on it, working it, dying on it. That makes ownership, not a paper with numbers on it.

We’re sorry. It’s not us. It’s the monster. The bank isn’t like a man.

Yes, but the bank is only made of men.No, you’re wrong there—quite wrong there. The bank is something else than men. It happens that every man in a bank hates what the bank does, and yet the bank does it. The bank is something more than men, I tell you. It’s the monster. Men made it, but they can’t control it.

The tenants cried, Grampa killed Indians, Pa killed snakes for the land. Maybe we can kill banks—they’re worse than Indians and snakes. Maybe we got to fight to keep our land, like Pa and Grampa did.

And now the owner men grew angry. You’ll have to go.But it’s ours, the tenant men cried.

We. No. The bank, the monster owns it. You’ll have to go.

We’ll get our guns, like Grampa when the Indians came.

What then?

Well—first the sheriff, and then the troops.

You’ll be stealing if you try to stay, you’ll be murderers if you kill to stay. The monster isn’t men, but it can make men do what it wants.

But if we go, where’ll we go? How’ll we go? We got no money.

We’re sorry, said the owner men. The bank, the fifty-thousand-acre owner can’t be responsible. You’re on land that isn’t yours.

Like these farmers, I can’t bring down the Machine. So, where are we to go? What are we then to do?

Here again, Karol Wojtyła and his friends provide a way forward. UNIA was not solely militant. While some members took up arms, others believed militancy and violence were not the right response. Instead of directly opposing the Nazis, they focused on creating a space for preserving and promoting Polish culture.

One tactic of the Nazi Machine was to convince Poles that they had “no public life,” that their culture did not exist apart from what would be imposed on them by the Germans. This feels eerily familiar. One of the Machine’s greatest weapons is its ability to destroy and invert culture.

At the time, while working in a limestone quarry, Karol Wojtyła was an aspiring actor and playwright. He was convinced that resistance to the Machine had to be creative rather than destructive. To this end, he partnered with Mieczysław Kotlarczyk, an older actor and theater director, to establish an underground theater company that would become known as the Rhapsodic Theater. In Wojtyła’s own words, the Rhapsodic Theater was “a protest against the extermination of the Polish nation’s culture on its own soil, a form of underground resistance movement against the Nazi occupation.”

Founded in 1941, the theater performed a series of plays centered on the spoken word. Given the necessity of secrecy, performances were staged in living rooms with minimal theatrics or staging. The company performed hundreds of shows, including a dramatization of Dante’s Divine Comedy and several of Wojtyła’s original plays, many of which have been preserved to this day.

But what was the point of the Rhapsodic Theater? It did nothing to slow down the Nazi military machine. At first glance, it might seem like they weren’t doing anything at all. Yet, the Rhapsodic Theater was, in fact, an extraordinarily active form of resistance. The theater ensured that Poles could still pursue flourishing and beautiful lives even in the midst of horror. They wanted also to ensure that something good remained when the Machine had swept through. In this way, the Rhapsodic Theater was an act of culture-making and, implicitly, an act of hope—hope that there is good worth pursuing and preserving.

I have been thinking a lot about hope recently. In 2025, the Catholic Church will celebrate a year of Jubilee, focused on hope. When Pope Francis announced this Year of Jubilee, he said, “In the heart of each person, hope dwells as the desire and expectation of good things to come, despite our not knowing what the future may bring.” Hope is the virtue necessary to pursue the good, even against improbable odds. The Rhapsodic Theater embodied this hope. It was a call to pursue the good, even when the possibilities of achieving it seemed especially grim.

I have become convinced that this is the role of writers and thinkers in the Machine Age, to help point our fellows toward the possibility of true flourishing in otherwise bleak time. We must participate in alternative culture-making. This is something I am learning from other writers, especially from Ruth Gaskovski, who uses her Substack, The School of the Unconformed, as a deeply positive project.

It also guides my current work as an academic and will shape the future work of the Savage Collective. Over the next few months, we’ll spend some time highlighting stories about people, practices, and institutions working to create new culture that resists the Machine with an aim to help people lead flourishing lives.

This may be an especially good time for guest writers to pitch into the project. We are also trying to make this embodied by hosting events in Pittsburgh. We recently hosted a Convivial Gathering, a multigenerational dinner, poetry reading, debate club, and singalong. Hope, in fact, is not something we have, it’s something we do.

I have decided this year to finally read through Steinbeck. I’ve read a few but have never read Grapes of Wrath or East of Eden. So, expect some more Steinebeck weaving through my work here.

Steinbeck is your man for this. After Grapes of Wrath and EoE (both masterpieces) you should do In Dubious Battle (set during a strike) and The Moon is Down (set in a European town during a foreign occupation). Both will be up your alley I think.

Nice reflection, Grant. Re: JPII: my wife and I were visiting an elderly priest friend in the hospital the day JPII died. I looked at my watch when we had to leave. Before we said goodbye, we prayed the Litany of Loreto. A happy memory: we were praying the Litany the moment the Holy Father died. Of course, we didn’t know it at the time, but made the connection later.