Redeeming BS Jobs

Excellence, Apathy, & The World’s Smartest Garbageman

In a recent post, Anthony Scholle wrote about Gen Z’s revelatory orientation toward modern jobs. His essay has been one of our most popular to date and recently prompted a response from another Gen Z writer. This essay is a guest post by our friend Amelia Buzzard who describes herself as “Gen-Z writer and mom in Upstate New York. Striving to be a clear lantern for God’s fire.” Brandon and I met Amelia at a recent gathering of Doomer Optimists in Margaretville, NY. You can read our summaries of the gathering here and here. This essay will be posted on her Substack Writer’s Blog(ck). A quick note. We have been receiving multiple submissions for guest posts. We will have atleast 3 in January. If you are interested in submitted something that you think will work on our Substack, reach out to us.

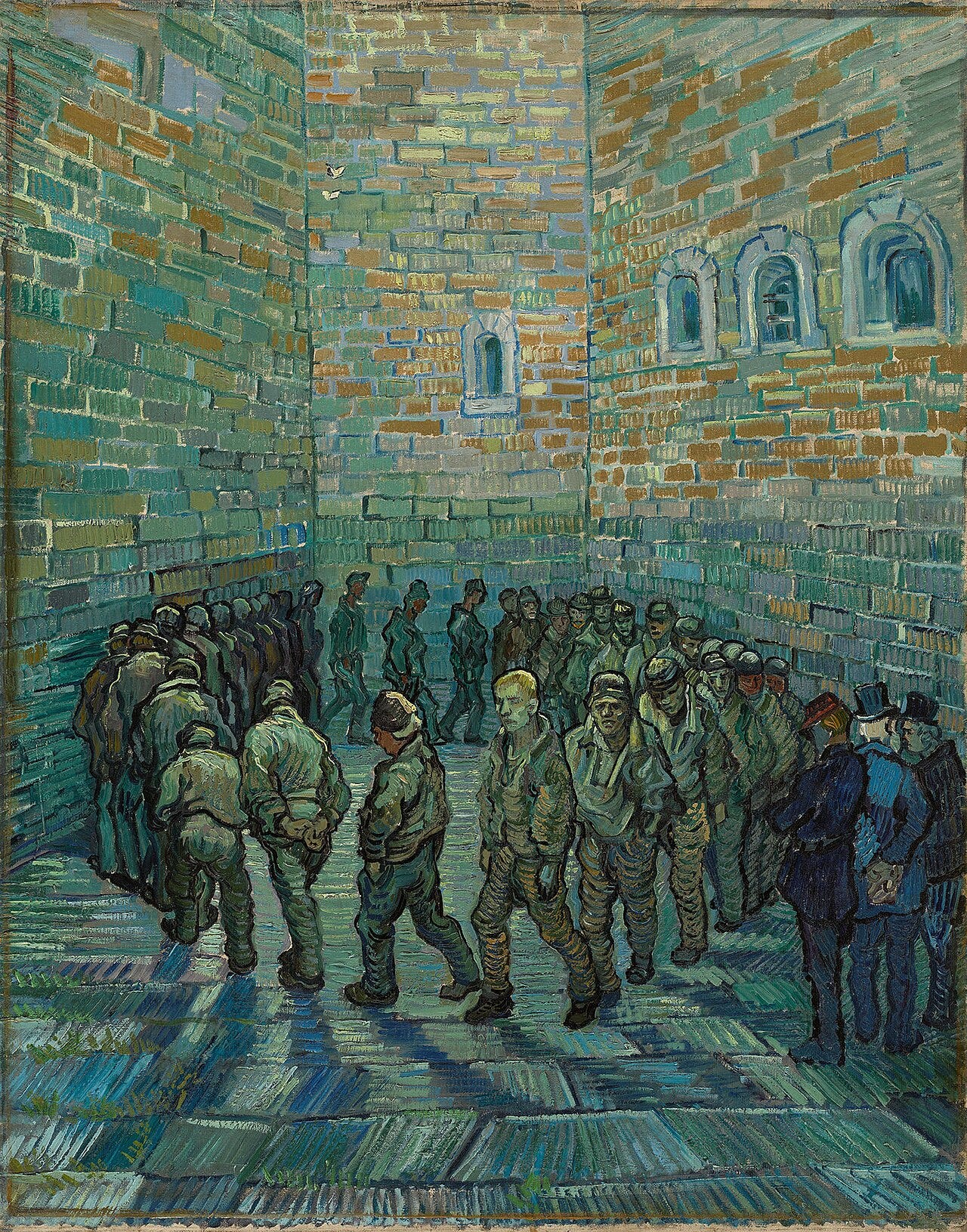

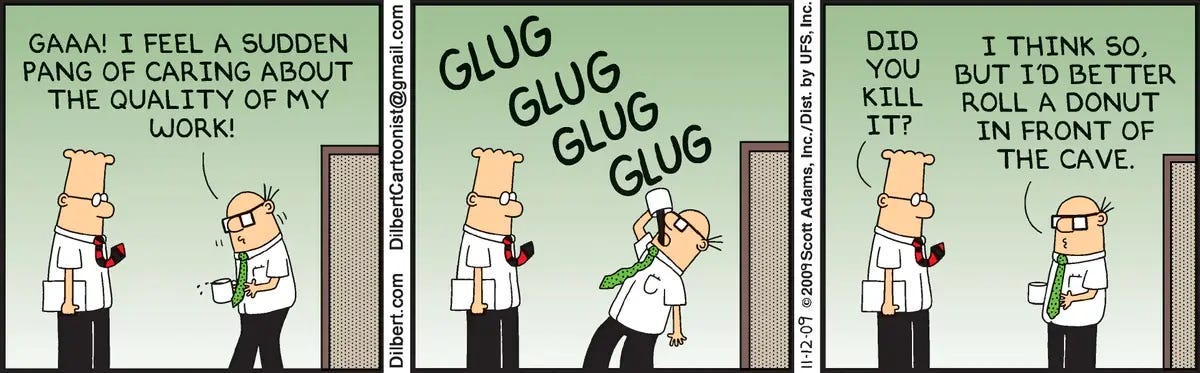

When I exited the workforce after two years as an early-career university administrator, I left with a deeper understanding of Scott Adams’ Dilbert.

As a teen, I had thought Scott Adams’ satire an entertaining fiction, perhaps a riff on one particularly hated office experience. But after working in a real office, I discovered why Dilbert had such universal appeal. Dilbert isn’t a fantasy. It’s a tragicomic reality, one many Americans are living in right now.

In a recent essay on Substack, a young auto mechanic named Anthony Scholle writes about Gen Z’s growing disillusionment with “cubicle monkey” jobs. He sympathizes with “quiet quitting”—a post-COVID trend in which jaded employees stop working but keep coming in to work. As Scholle observes, quiet quitting was a litmus test for many: “Realizing that they could remain employed while not doing their jobs, Gen Z confirmed their suspicions that they had been swindled into doing pointless work.”

Scholle’s critique resonated with me. It articulated something I had begun to sense during my own short-lived foray into office work: the quiet despair of doing nothing while pretending to do something. Like many in my generation, I had grown up believing that hard work and excellence would be rewarded. But how was one supposed to respond when the work itself felt hollow—when the system seems designed to suppress excellence rather than foster it? Nobody had prepared me to deal with that reality.

I was fresh out of college and had followed my husband to a remote Western town so he could pursue his master’s degree. I had a part-time job teaching German at a rural school but needed to find some full-time work. The first thing I noticed about my new town’s Indeed.com scene was that due to a boom in California transplants, cleaning ladies earned over $20/hr. So, I rolled up my sleeves and took a full-time job cleaning vacation homes at a ski resort. It was physically demanding work that kept me fit. It was also useful training for someone with a head so high in the clouds you could’ve buried me up to my neck without my noticing.

Once I learned the difference between a mop and a broom, however, cleaning got boring. I started looking for something more skilled. “Skill” in my mind meant “office.” So I applied for a job posting for “Admin III” at the local university.

What did “Admin III” mean? I’m still not sure. I found out later that my predecessor had spent most of her time knitting. By the end of my stint, I too would take up the art of yarn (crochet, in my case). But I’m getting ahead of myself.

When I traded my blue collar out for a white one, the 9-to-5 grind turned into an exercise in endurance sitting and my $21/hr wage turned into $18.50 plus benefits, which I quickly realized that, being a healthy person in my early 20’s, I would not use. My new job required no more skill than my last. It certainly required much less work.

First, it took a week for me to get integrated into the university computer system. After taking a few mandatory video trainings on sexual harassment and cybersecurity, I had nothing to do. I figured that once I had a NetID, things would change. They didn’t. Although I had brief flurries of activity, much of my workday was empty, and I couldn’t accept that my duties didn’t fill my hours. My first-grade teacher Mrs. Stettenbenz had brainwashed me early in life with the mantra “Do your best your very best and do it every day,” and I still believed that was the best way to live.

So, I began to create tasks to fill the time. I taught myself Adobe InDesign, so I could revamp the semesterly department magazine into something that looked semi-elegant. I read all the papers the professors were publishing on emergency flood response and consumer drug preferences so I could edit the abstracts down to shorter blurbs for the magazine. I became an amateur journalist to write obits for emeritus professors and profile alumni. I designed six updated posters for the department walls, reorganized its website, scheduled Instagram posts, made a logo for an extension initiative, created a 20-page promotional booklet. I learned CSS. None of this was listed in my job description.

In my mind, I had transformed “Admin III” into a Creative Director of Communications. Although I was ostensibly paid for my sparse administrative duties, the majority of my time and effort went not towards the job I had been given, but the job I had created for myself.

The quest for something to do reached its zenith around Christmas when I sketched our building and turned the artwork into a thank-you card to send to private donors.

It had been a year. I steeled myself and asked for The Raise that would make it all worthwhile.

I bit my fingernails for a month. After the paperwork had squeezed through 20 levels of HR approval, my manager got back to me with the news—I’d gotten my raise! But it was not The Raise. Instead, due to a policy that capped raises at a paltry 4%, the reward I’d been hoping for amounted to about $20 more per week. Meanwhile, inflation had risen to 5% that year. In real wage terms, my “raise” amounted to a slight pay cut. I soon realized that the only way to advance within the state university system was to job-hop continually and apply only for jobs classified under a unionized sector.

This realization marked my turn to cynicism. When I found out I was pregnant a few months later, I remembered those benefits my employer had touted and decided to stick it out for another year so I could get my hospital bills paid.

I cut my work down to satisfy the bare minimum of Admin III’s sparse duties and filled my time with mom stuff. In other words—I “quiet quit.” In my first trimester, I would shut my office door, puke in the trashcan, bunch my coat up into a pillow, and take a nap on the floor. In my second trimester, I spent most of my time chatting with kindly professors about their families, or discussing sociology theories with a coworker. In my third trimester, I listened to birthing podcasts and researched government-subsidized programs for low-income moms.

I crocheted a bunny.

Reflecting on this saga, I think the worst part was the loss of faith in my employer’s standards. I believed, in the spirit of American meritocracy, that they were starting me at a low salary so I could prove my value and then earn my just reward. When it turned out the system was paying me to work two hours ,then sit in my chair ‘til kingdom come, I felt betrayed.

I had three options: (1) Conform to the system’s incentives by lowering my own standards, thereby aiding it in its implicit mission to extinguish any spark of human excellence, or (2) rebel against the system by cultivating human excellence—but without proper compensation. Or (3), quit.

I now realize that, had I heeded the wisdom of Dilbert, I would have seen this coming.

The first option—conforming to the system—is represented in the comic by a balding, coffee-carrying engineer named Wally. He’s a genius at milking the system, the bane of middle management due to his ability to manipulate workplace policies for his own personal gain. I became a pale shadow of Wally when, during pregnancy, I “quiet quit.” I don’t recommend this option.

The second option—resisting the system through excellence in one’s work—is represented by the eponymous Dilbert, who manages to remain in the office without becoming of it. Despite his workplace’s lack of appreciation for his enthusiasm, he genuinely loves engineering and often comes up with inventions on his own time. Although he’s often sarcastic, he retains a commitment to excellence that most of his coworkers lack.

The Dilbert option is better than the Wally one. Even within jobs intent on punishing the good and promoting the bad, there’s room for human agency. We can test the limits of our jobs to see if we can push them outward into excellence. If someone can “quiet quit” without anybody noticing, he can also strive silently towards good. Pre-pregnancy, my go-getter attitude did not get me the raise I had hoped for, but I could still spread out four magazines on my desk and demonstrate how my design skills had improved from first to last.

But for most of us, there’s only so long we can operate as a Dilbert before we find ourselves courting the third option: quitting. In Dilbert, this path is represented by a third character, more obscure: The World’s Smartest Garbageman.

This character is enigmatic. We know very little about him, except that he is a genius who can fix Dilbert’s failed inventions after a cursory glance at the crumpled-up calculations in the bin. This aura of mystery reveals his position in relation to the comic. Dilbert is about an office; the Garbageman doesn’t work in an office. When Wally, Dilbert, and the Pointy Haired Boss are busy buttoning their shirts and smoothing their ties, the Garbageman is out on the street making his rounds of the bins.

During the last year or two, many commentators have pointed to the rise of populism worldwide, the growing disillusionment with institutions, from “coastal elitism” to “Rhino” politicians, to most recently, the healthcare industry. At the same time, we’ve seen a growing glamorization of homesteading, country music, and a homegrown Midwestern aesthetic.

The Garbageman seems to be having a moment in our culture.

But Scott Adams wisely chose a profession for this character that is difficult to romanticize. Just because Dilbert’s office isn’t fair doesn’t mean the world outside is any better. The World’s Smartest Garbageman has to make tradeoffs when he quits the office world, sacrificing his cultural status and physical ease for his freedom.

In the end, the Garbageman isn’t all about his job—and that’s just what attracts us. We admire his Zen-like equanimity, his cheerfulness as he inhales rotten fumes. He shows us that if we want the perfect job, we’ll always be unhappy. The answer lies not in constant critique and complaint but in redeeming our situation through character, principles, and personal integrity.

So, in conclusion, I’ll repeat my first grade chant, that battle cry against the mediocrity of modern office life:

“Do your best, your very best, and do it every day.”

If we can say that in good faith, we’re still human.

I am very grateful for this write up and particularly for being introduced to The World's Smartest Garbageman. He's going on the fridge.

Excellent.

I am reminded of the difference my husband (a nuclear chemist) has experienced between his postdoc at a fully-funded research position at a National Lab vs. where he is now in the private corporate sector. In the former position, he noticed after a year or so that shitty and lackluster work would be put up with in the group (from even PhD contributors) because there is no real incentive in the national lab research model to do good work. It's like academia, in that as long as some rich person or government is keeping the paychecks coming and a minimal effort is put forth to keep the thing churning..... no one really cared about doing better. Where he's at now--for all people rant about the greed of private companies, capitalism, etc etc etc—there is an actual fire under everyone's bottoms to do good work. If they don't, the cancer patients aren't helped and more to their own interests, they could be out of a job if the product doesn't materialize from an idea to a workable therapy and make money for everyone. Case in point, 40% of the company was laid off last year abruptly... and while that was a collective failure, it sure makes it much more real that excellent work on the part of all = keeping your jobs! Something I think about in regards to places concerned with profit whenever I hear about the BS nature of academia/universities/some nonprofits, honestly (I've worked at one, he he).

*Not that private companies don't have their own BS jobs! Surely there's plenty of HR and administrative jobs to keep the bureaucracy happy... but I think it's mostly contained to those areas in much of the for-profit sphere.