In this data brief, we introduce a new writer to our Substack. Brendan Case is the Associate Director for Research at the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard University. He is a theologian with an interest in the state of men in a post-industrial economy. He and Grant have written several academic articles together and co-authored this piece. We are hoping that Brendan contributes more pieces in the future.

One of the most talked about aspects of the most recent presidential election was the ground that Trump gained among Black and Hispanic voters. Among some demographics, the shift was truly stunning: Latino men in Texas preferred Biden by a margin of 17 points in 2020, but favored Trump by a margin of 11 points, a remarkable 28-point rightward shift. The gains were especially significant among non-college educated minorities; Trump gained 5 points from 2020 to 2024 among non-White Americans who have not gone to college, as opposed to a single point among the minority of college-educated Americans. This trend seems to suggest that the Democrats’ stranglehold on non-white American voters is beginning to break.

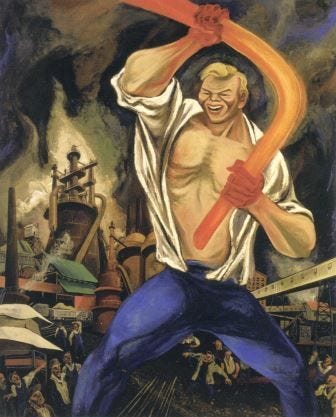

In fact, this election may signal the emergence of increased class solidarity in voting across racial and ethnic lines. This may be driven by the recognition of class interests that transcend racial and ethnic categories. Americans of all races without college degrees face a similar set of challenges, such as the interrelated issues of median-wage stagnation and the rising cost of living, the economic and social costs of mass (and especially illegal) immigration, and their day-to-day exposure to the costs of the recent progressive fad for decriminalizing public disorder and anti-social behavior.

We hear much in the United States about racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes related to health and well-being. These are important to study and consider. Grant has written several papers examining racial and ethnic disparities in various health-related outcomes. However, the discourse over race and ethnicity can obscure an arguably more important driver of inequities across the United States in terms of health and well-being namely class.

Clearly, these factors are closely related, inasmuch as race/ethnicity and social class are closely correlated in America today. In Grant’s own work focused on health outcomes, he often identifies a complicated relationship between class, race/ethnicity, and outcomes. For example, in a paper that is currently under review at a major academic health journal, he found overall racial disparities in hospitalization rates between White and Black Americans. But for people living in the most socioeconomically deprived communities, White and Black patients had very similar rates of hospitalizations. These findings suggest that being poor in the United States is challenging for all Americans regardless of race.

We have been working on a series of analyses using the first wave of data from the Global Flourishing Study (GFS), which includes 202,000 individuals in 22 countries around the world and aims to track these individuals through four additional waves of annual follow-up. The GFS is co-led by the Human Flourishing Program, where Brendan is the Associate Director for Research, the Institute for Studies of Religion at Baylor University, Gallup, and the Center for Open Science. The data for each country in the sample, including the United States, is nationally representative, and covers a wide range of dimensions and drivers of well-being, including questions about life satisfaction, physical and mental health, meaning and purpose, character and virtue, close relationships, and financial stability. All of these items can be aggregated into a scale used to measure “human flourishing,” a type of well-being.

We have initially analyzed the U.S. data from the GFS on twelve items assessing six dimensions of flourishing among prime-working-age (25-55 year-old) men, and looked in particular at the relationship between race/ethnicity and class and human flourishing. (In future work, we want to dig deeper into the sense of hope, meaning, and purpose among this demographic.) We ran simple regression models with the flourishing scale as the outcome and race/ethnicity and class as predictors, controlling for age, nativity, and rurality. In this case, class was measured as whether or not the person had completed a bachelor’s degree, a very common measure of class.

We found what we broadly expected, namely that class was strongly correlated with the flourishing measure, but race was not.1 The coefficient tells us that those with a bachelor’s degree score about 1/2 (0.544) a point higher than those without on the 10 point flourishing scale. This may seem small but is actually a relatively large effect size given the limited variation in overall flourishing scores.

This finding is consistent with much prior work in this area, such as Anne Case & Angus Deaton’s exploration of the explosion in recent decades of “deaths of despair” (from alcohol poisoning, drug overdose, and suicide) among less-educated white men in particular. We think in another post we’ll do a much deeper literature review examining the relationship between class, race/ethinicity, and well-being.

But suffice it say, growing class solidarity would be a positive development as those with shared class identity likely share more material and well-being interests than we are lead to believe in contemporary political discourse. Trump may prove to be an unlikely source of growing solidarity among working class Americans regardless of race and ethnicity

In statistical analyses, a “pvalue” of less than 0.05 is considered “statistically significant.”

One of the interesting things, I think, is how de-racinated Trump's 2024 (and 2020) platforms were compared to his 2016 platform. He likely came to believe that it was no longer possible to win on the basis of white populism due to demographic changes -- too much immigration, too much of an aging white population which had too few children to win on that basis moving forward -- and therefore he had to shift away from white populism and toward broad-based raceless economic populism. Indeed, this is similar to Latin America, where there are "right" and "left" parties but only on the basis of economic and religious positions, not race. Given demographic realities elections will be held on this basis moving forward unless Trump kicks out tens of millions of illegals, which I do not think will happen.

I wonder what happens if things don't get better for the working class of any race.